Surname is everything for the “upper castes,” as it helps them project their self-proclaimed superior caste status onto society at large. Without it, they would have to resort to other methods, such as verbally declaring their caste identity, in order to be recognized as such. It is their traditional caste-laden surnames that allow them to bask in the glory of their caste status.

The “lower castes,” on the other hand, lack any status worth preserving or projecting under the caste system. Therefore, they do everything they can to hide their lower caste identities. This is achieved by either dropping surnames altogether, adopting caste-neutral surnames, creating new surnames, or adopting surnames traditionally associated with the “upper castes.”

For the “upper castes,” their traditional surnames function as trademarks representing their distinct caste status and identity. They treat these trademark surnames as their intellectual property and resent their adoption by the “lower castes,” particularly the Dalit community (historically labeled as “untouchables”). They argue that after spending decades cultivating the superiority associated with their surnames, they cannot allow them to be degraded by being adopted by individuals of lower caste status.

In other words, in the factory of caste, where the product of casteism is manufactured, the surname of the casteist manufacturer serves as the trademark. This trademark surname represents both the act of manufacturing casteism and the product of casteism itself. The casteist manufacturer does not want to lose the caste-based identity and status associated with this trademark surname. But what happens if the consumers of casteism start adopting these very trademark surnames to shield themselves from the product of casteism and from being identified as consumers in the first place?

Surnames & Caste: A Historical Perspective

In Indian society, surnames often signify one’s caste, gotra, and lineage. They serve as markers of identity that perpetuate the hierarchical structure of the caste system. However, it is crucial to recognize that a surname does not definitively indicate or determine a person’s caste. Over time, legal jurisprudence has emphasized this distinction to mitigate caste-based discrimination.

For example, Indian courts have repeatedly clarified that while surnames may provide clues about an individual’s caste, they are not definitive proof of caste identity. This legal perspective challenges the traditional association of surnames with caste and offers some protection to those who might otherwise be targeted due to their perceived or actual caste affiliations.

Legal Jurisprudence and Surname-Caste Disconnection

Legal cases across India have demonstrated that surnames are insufficient as sole evidence for determining caste. Landmark judgments have highlighted the importance of caste certificates, genealogical records, and community recognition over mere surname usage in establishing caste identity. The judiciary’s stance reflects an attempt to counter caste-based prejudices embedded in societal norms. However, this separation of caste and surname often fails to translate into everyday social interactions, where surnames remain a potent indicator of one’s social standing.

Dalits have frequently faced accusations of degrading traditional upper-caste surnames when they adopt or modify these surnames. Critics argue that this practice diminishes the sanctity of upper-caste identities. However, such accusations overlook the social realities and legal implications faced by Dalits in their interactions with others.

Case Study: Analyzing the Surnames of Scheduled Caste Individuals in National Scholarships, Competitive Exams, and Parliamentary Elections

There is one important instance where individuals belonging to the Scheduled Castes community are required to produce their caste identity certificates issued by the government for verification purposes. This occurs when they avail themselves of their constitutional entitlement to reservation in admission to educational institutions, government jobs, and elections to legislative bodies. The caste identity certificates contain the legal names of these individuals, which include their first names and corresponding surnames, if any.

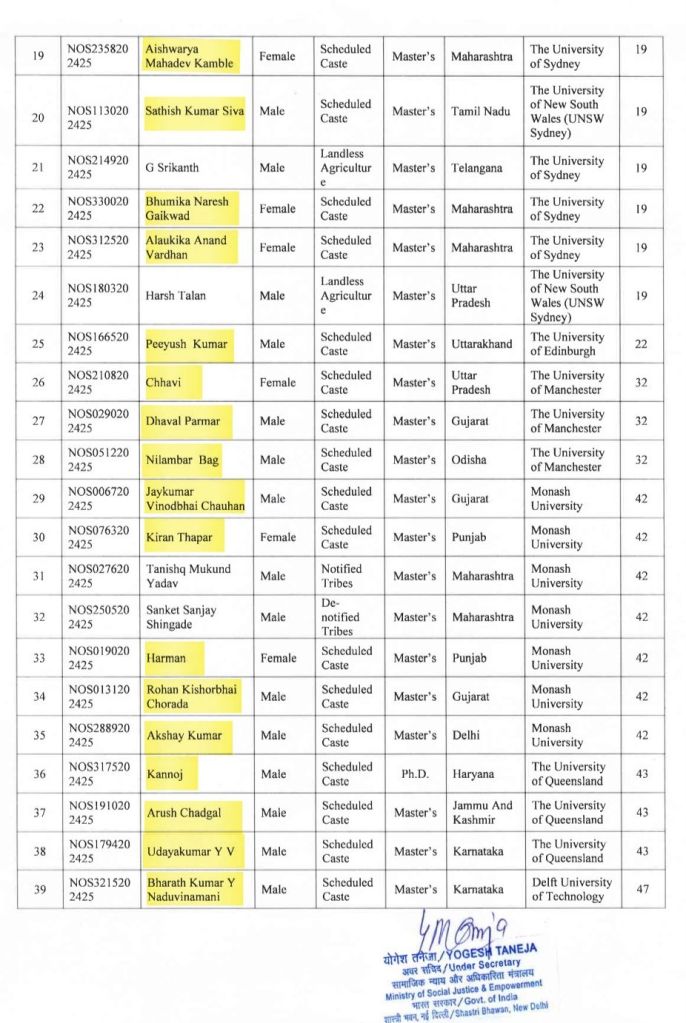

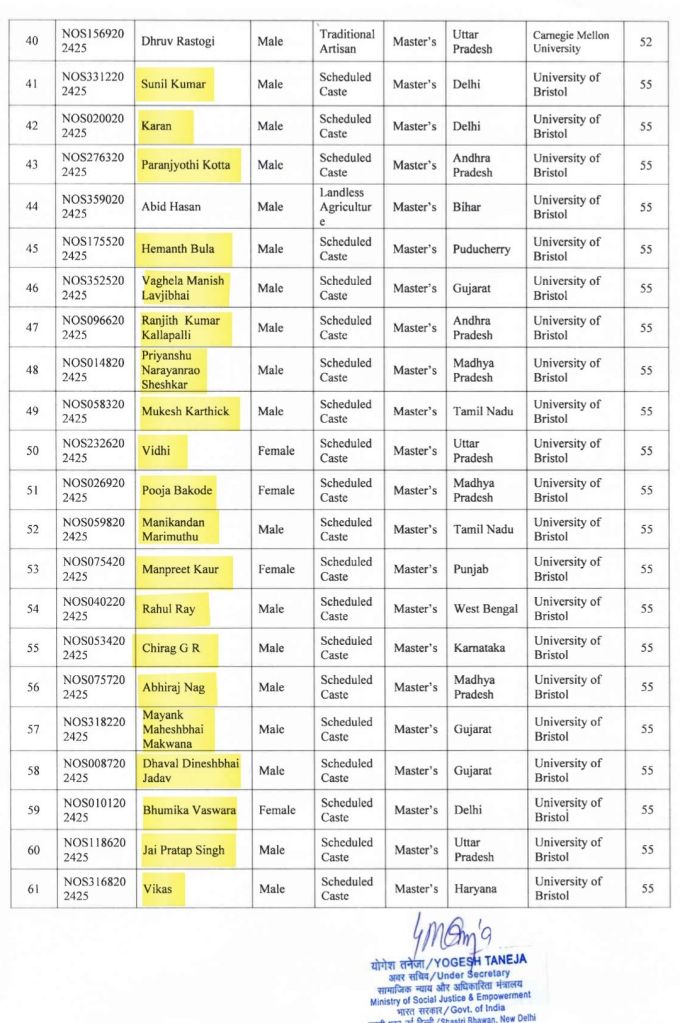

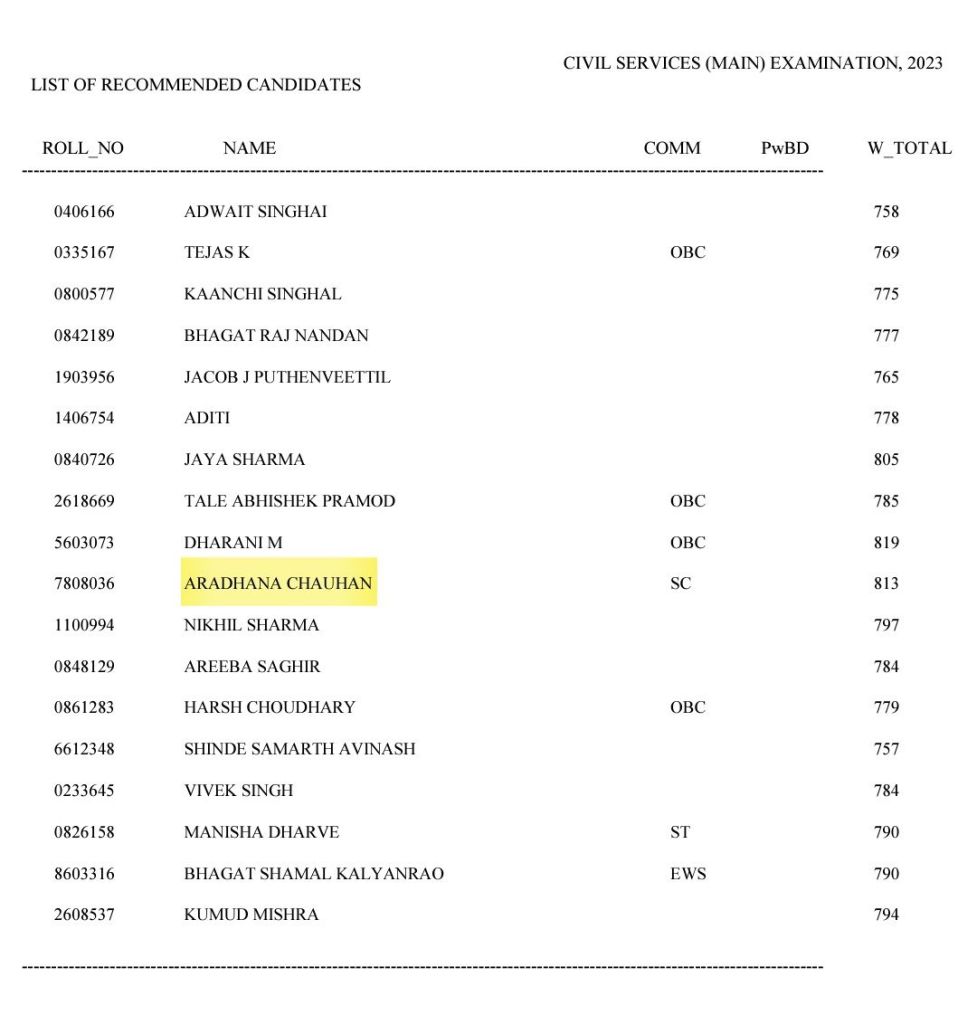

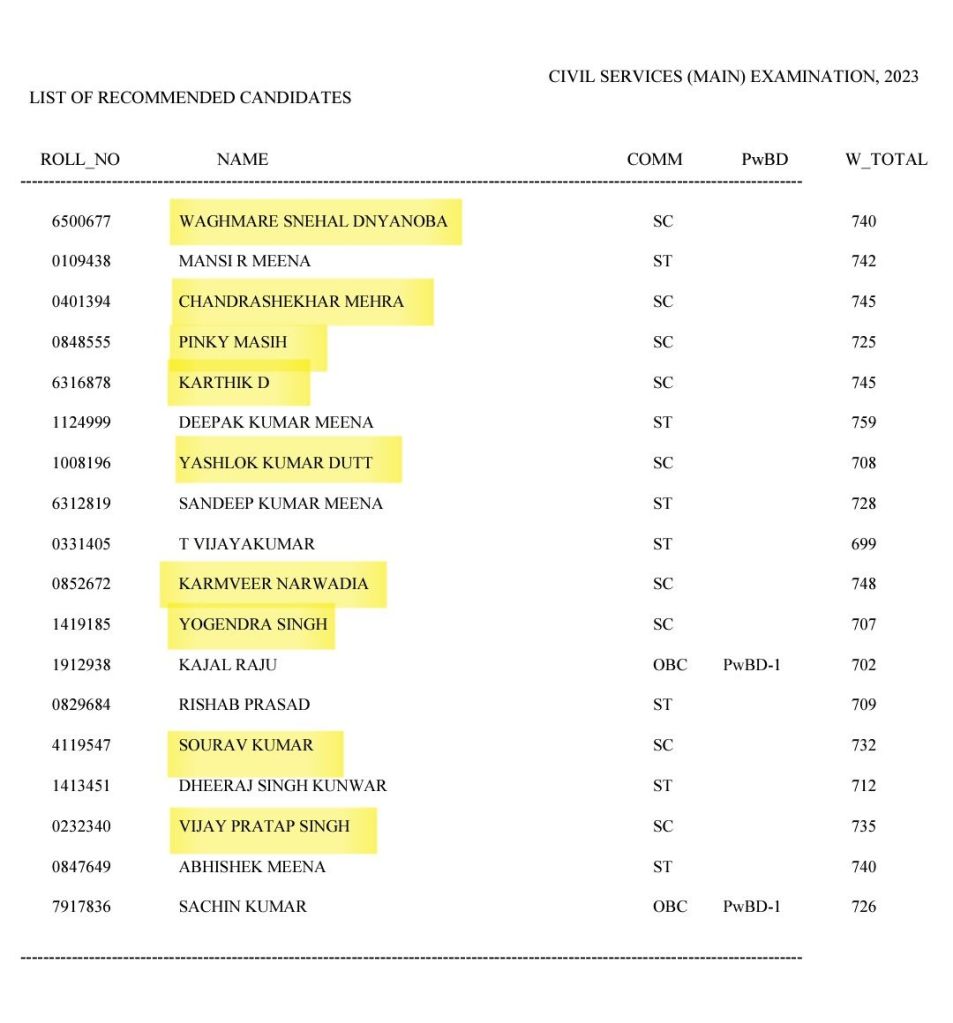

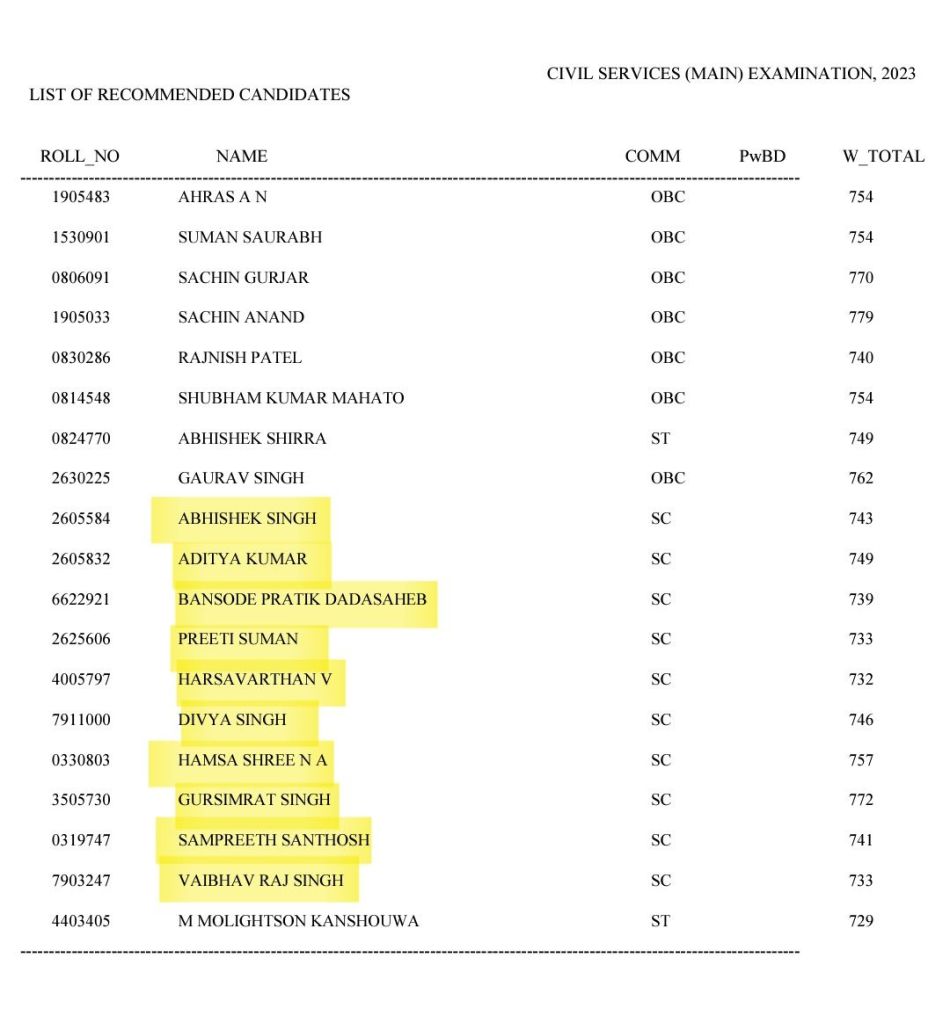

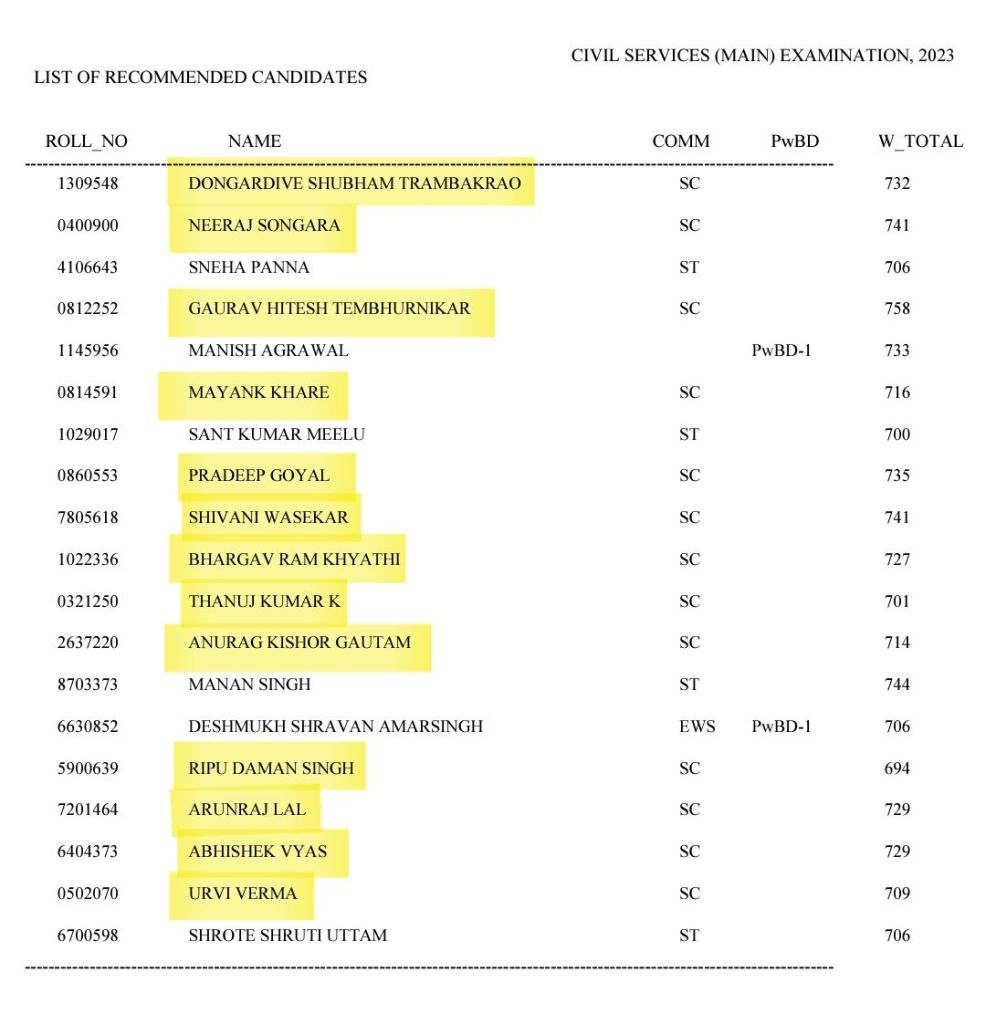

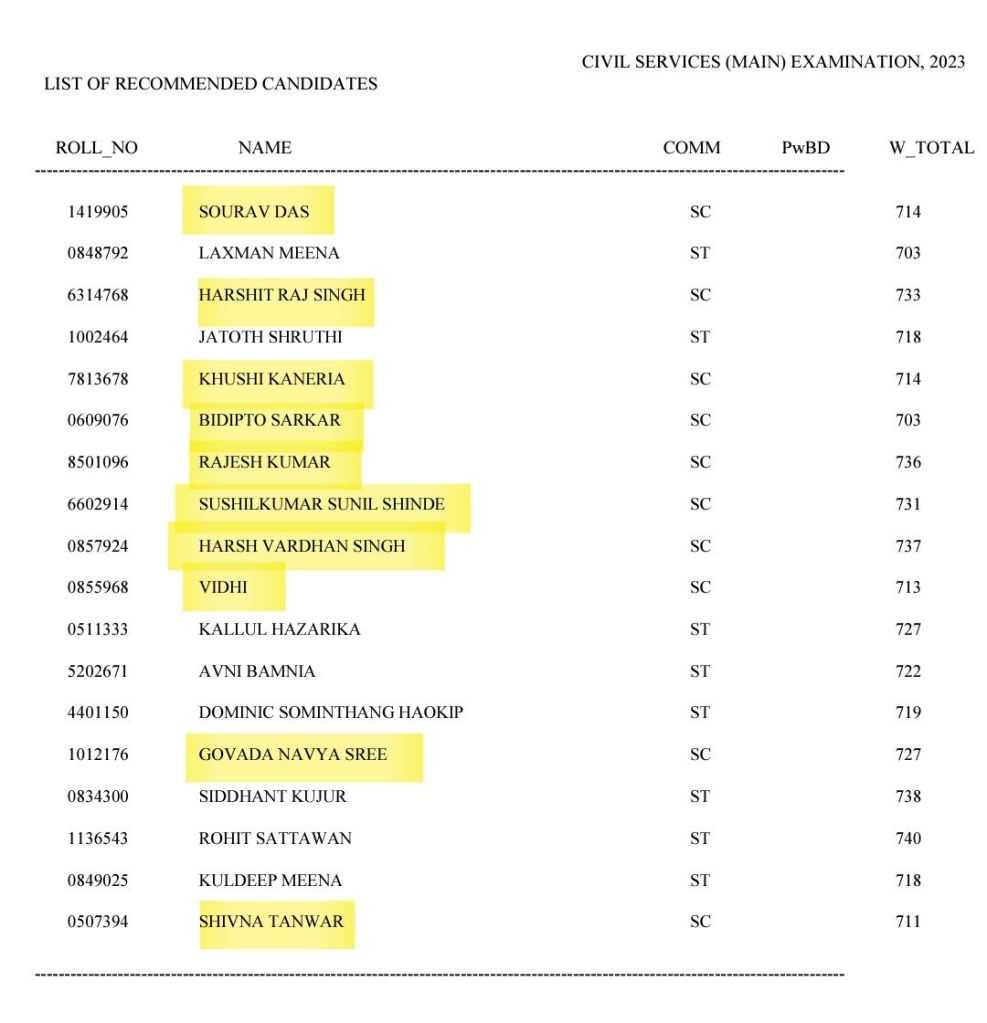

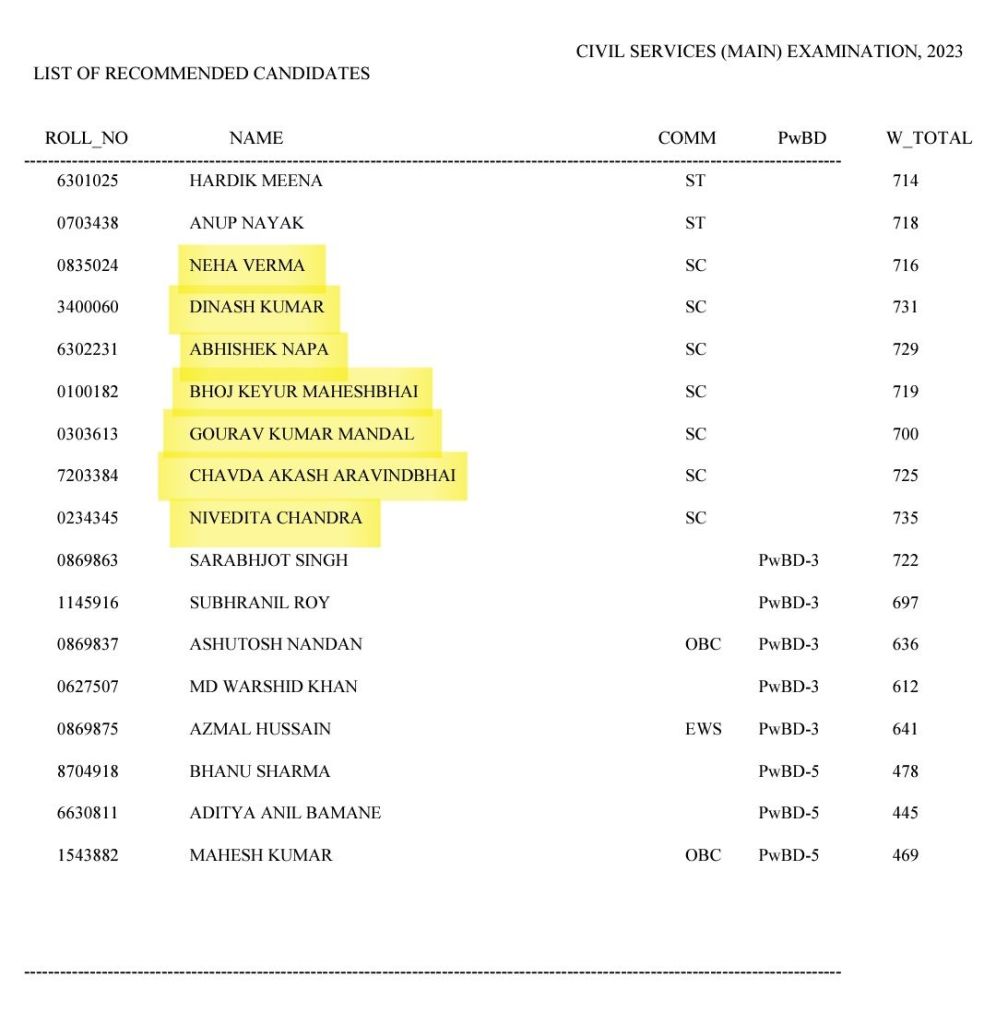

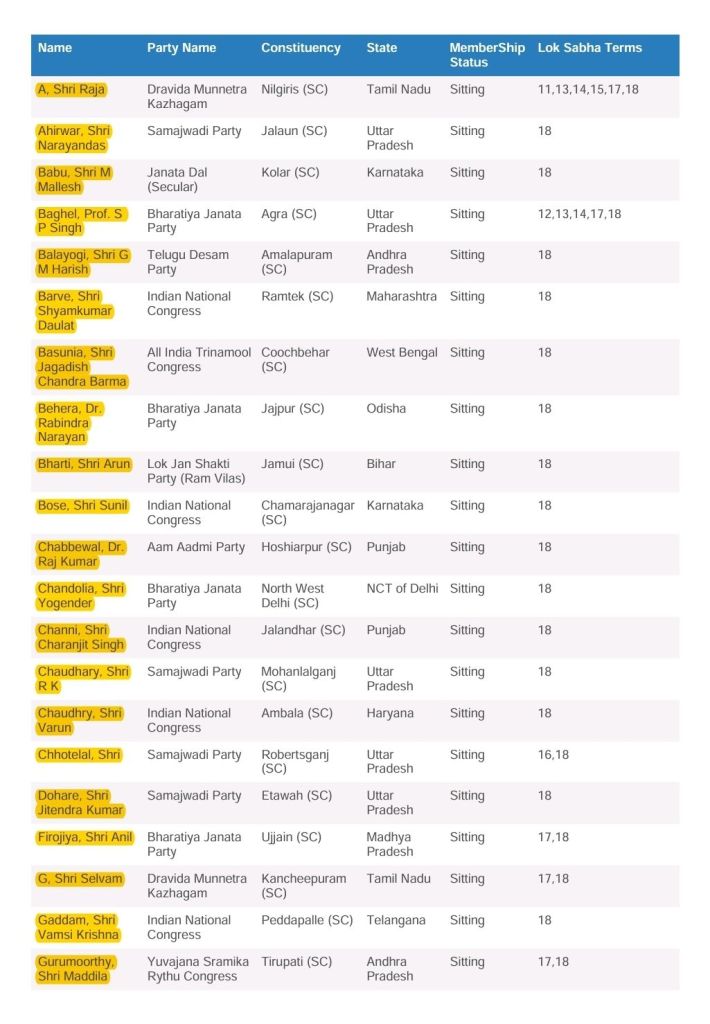

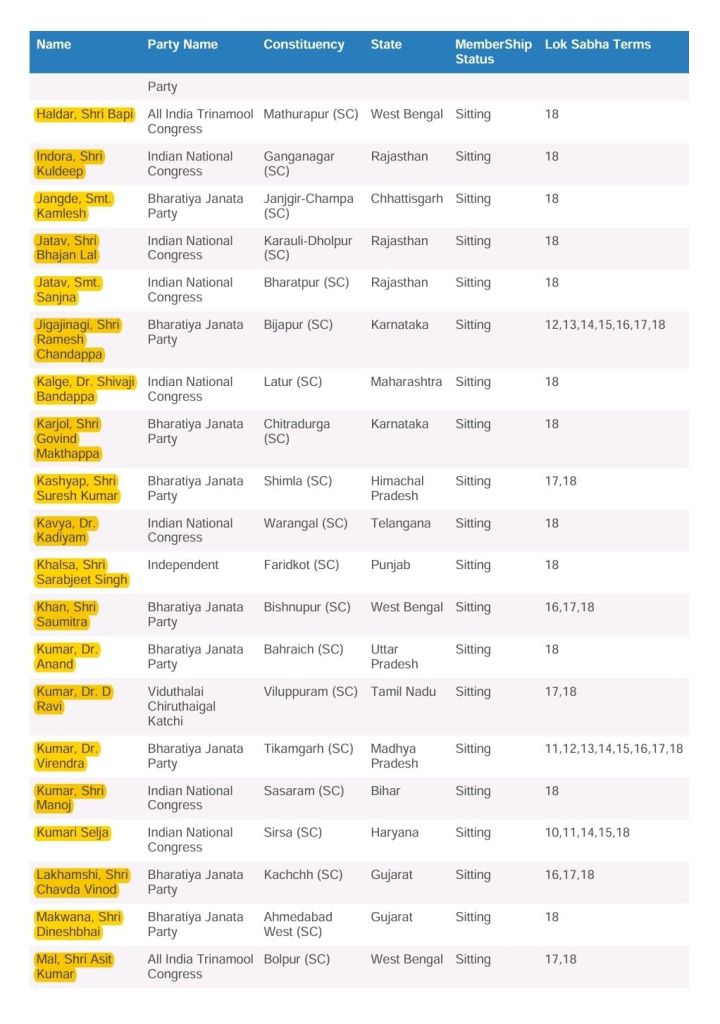

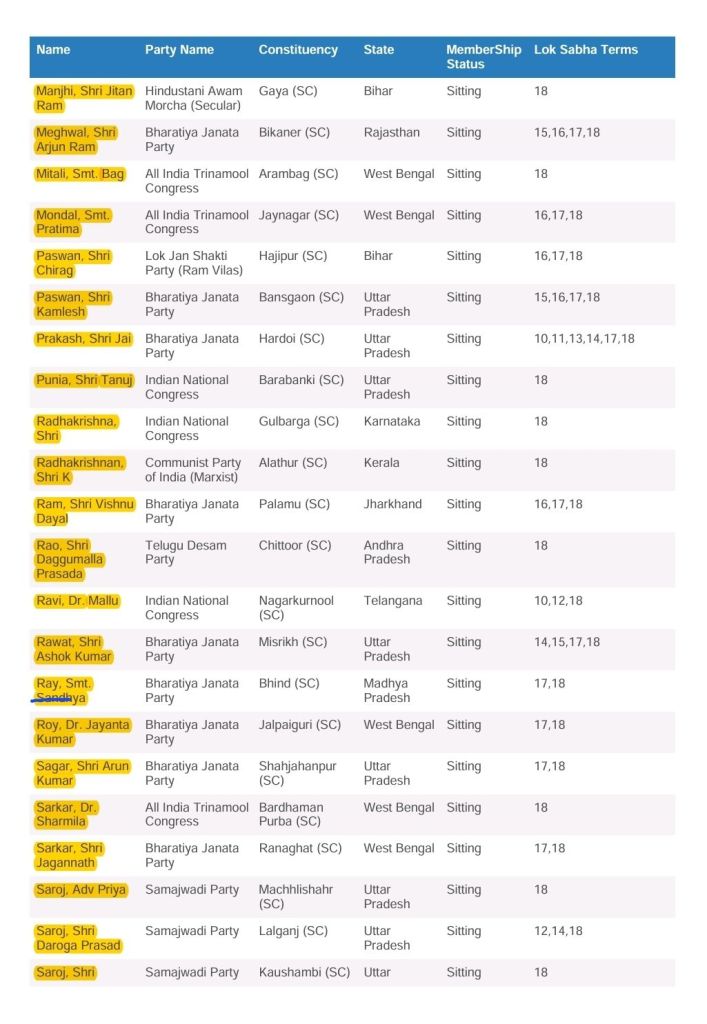

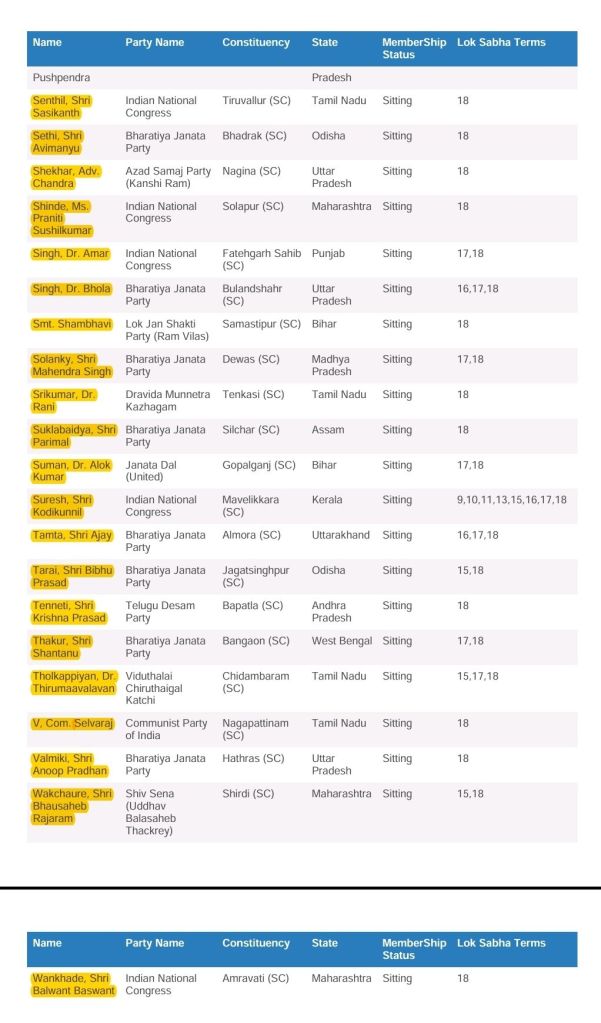

This case study uses the legal names of Scheduled Caste individuals who are candidates for the National Overseas Scholarship (NOS) Scheme of the Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment, Government of India; candidates for the Civil Services Examination conducted by the Union Public Service Commission; and elected Members of Parliament (MPs) in the Lok Sabha of the Indian Parliament. This is done to encompass names at the national level, as candidates for these scholarships, examinations, and institutions come from every state in the country. Moreover, these institutions conduct a strict evaluation of the validity and authenticity of the caste identity certificates submitted by these individuals, leaving negligible scope for falsifying caste identity.

1. Legal Names [First Name + Surname (if any)] of Scheduled Caste Candidates under the National Overseas Scholarship (NOS) Scheme

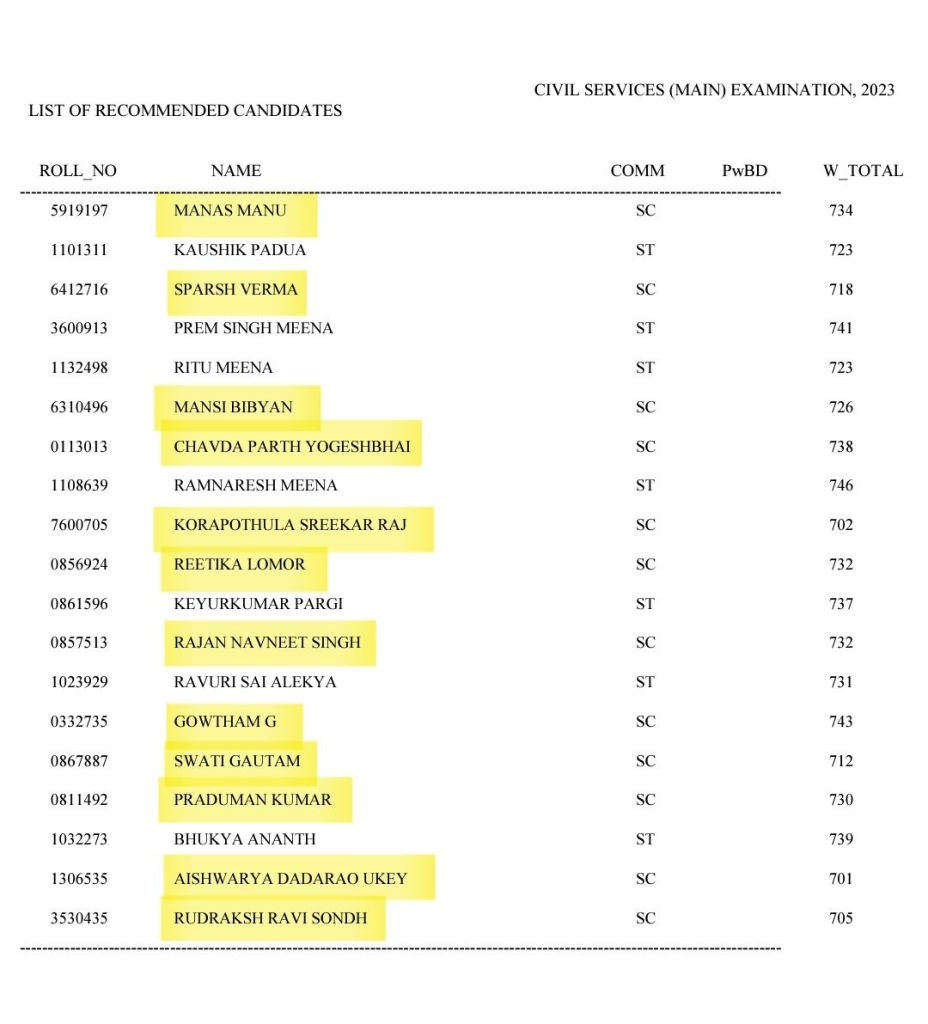

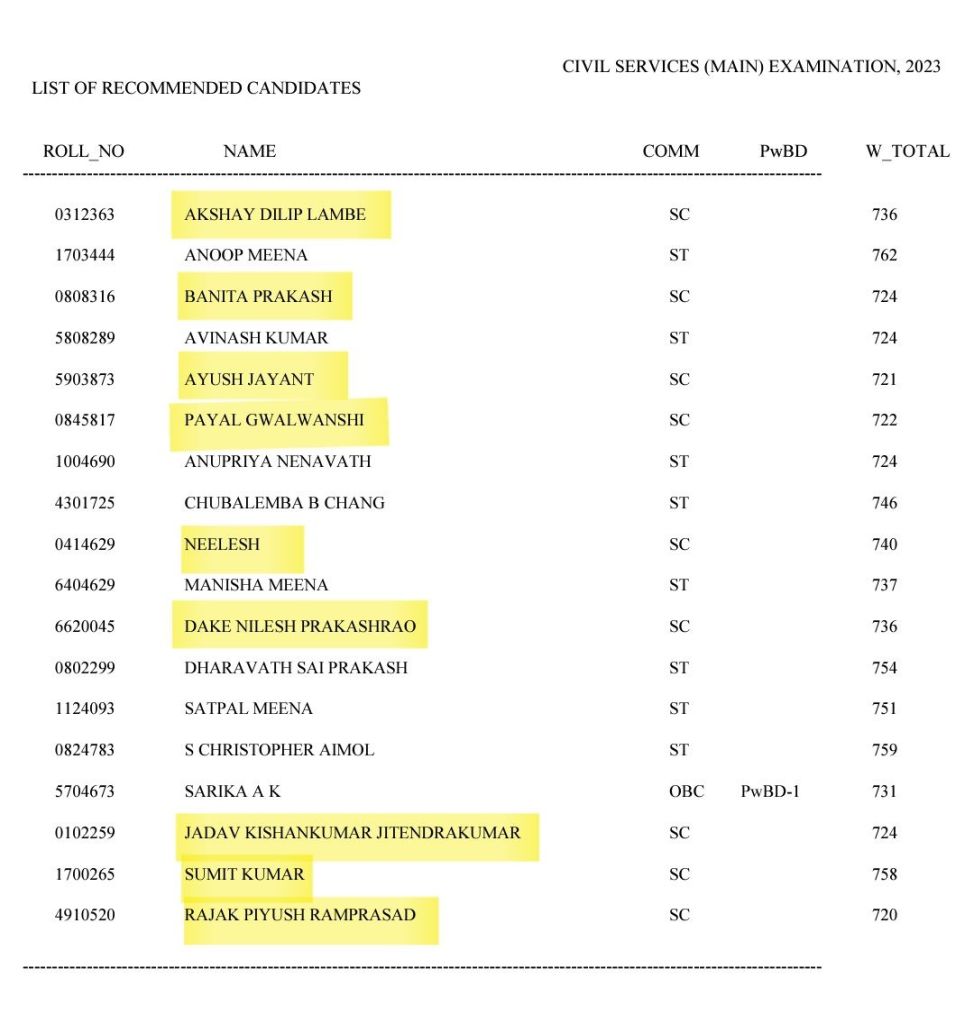

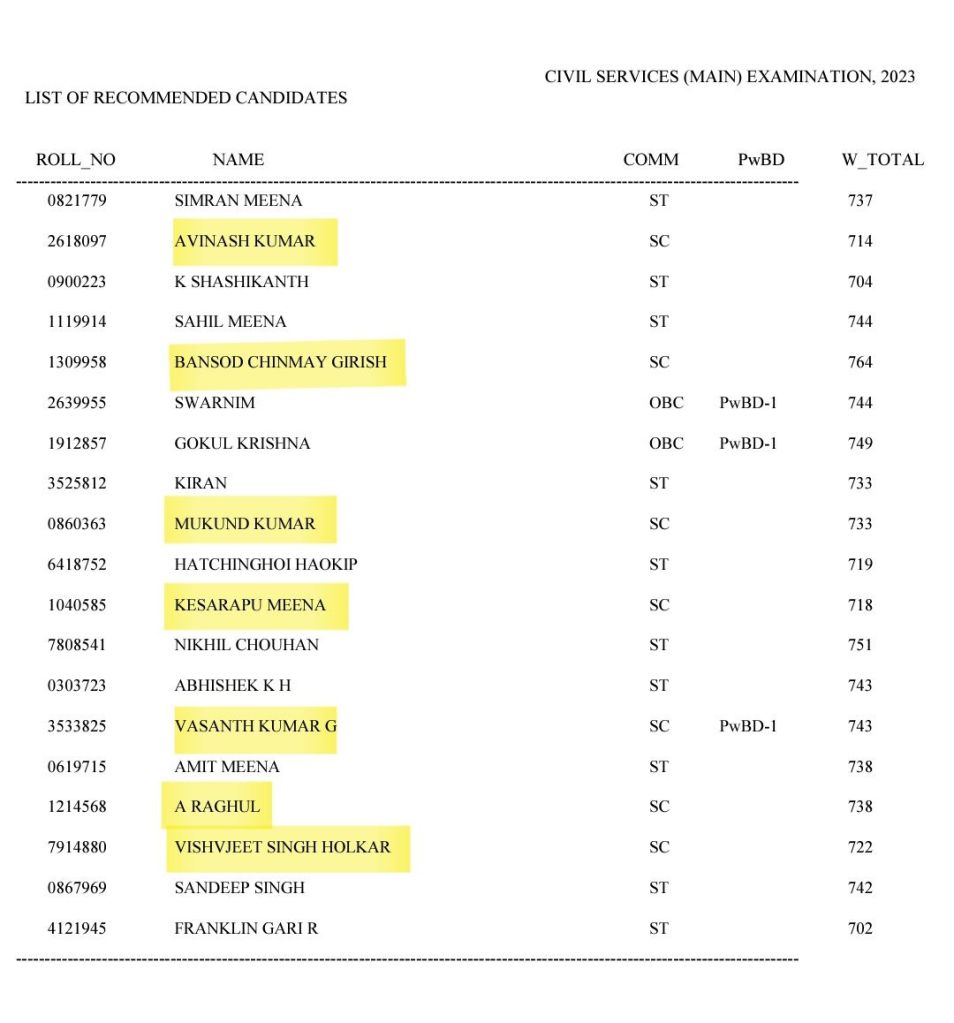

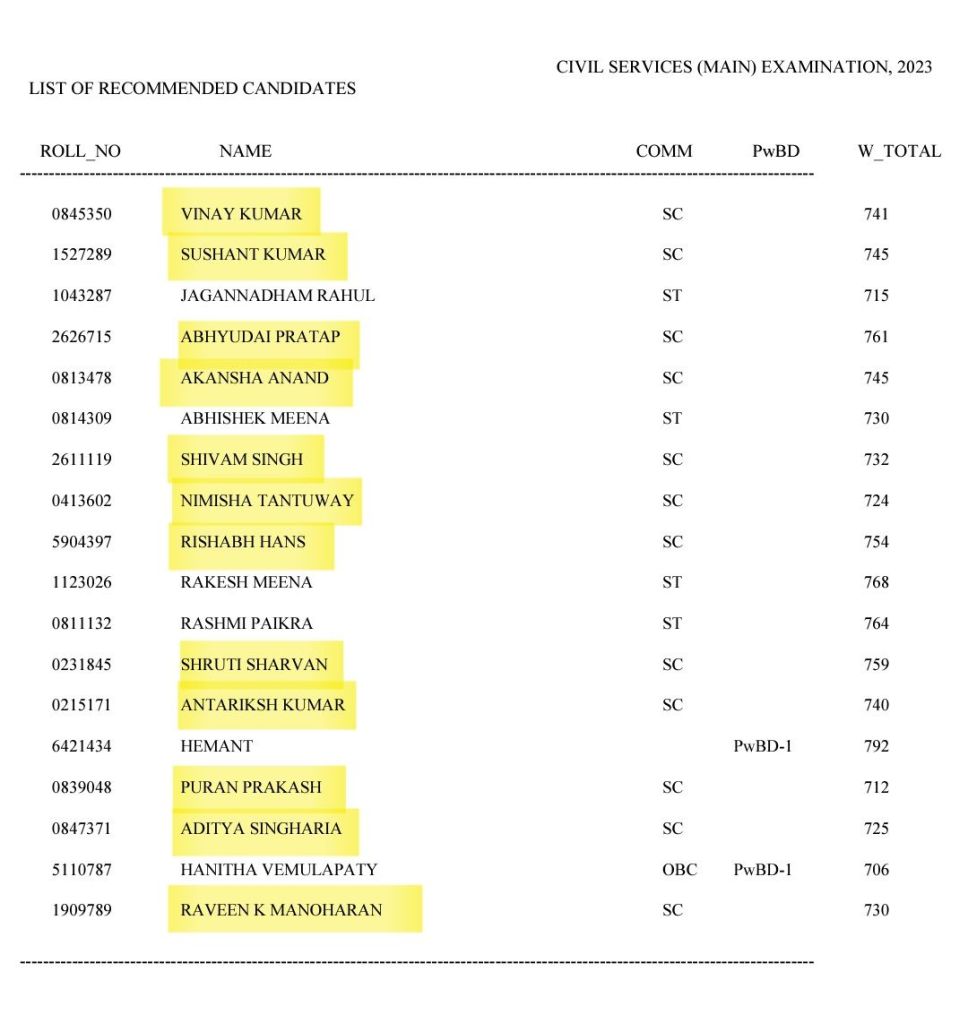

2. Legal Names [First Name + Surname (if any)] of Scheduled Caste Candidates for the Civil Services Examination, 2023

3. Legal Names [First Name + Surname (if any)] of Scheduled Caste Members of Parliament (MPs) in the 18th Lok Sabha of the Indian Parliament

These legal names [First Name + Surname (if any)] can be categorized based on the presence and nature of the surnames. They can be categorized into five types: (1) names that do not include any surnames, (2) names that include caste names as surnames, (3) names that include caste-neutral surnames (e.g., Kumar, etc.), (4) names that include surnames traditionally associated with the so-called upper castes, and (5) names that use an entirely new word as a surname (e.g., using a second name as the surname or the first name of a parent as the surname).

| Categories | Names + Surnames |

|---|---|

| No Surname | Chhavi Harman Adarsh |

| Caste Names as Surnames | Anil Singh Jatav |

| Caste-neutral Surnames | Akshay Kumar Jagriti Singh |

| Upper-caste Surnames | Kiran Thapar Jaykumar Chauhan Abhishek Kataria Chandrashekhar Mehra Yashlok Kumar Dutt Sparsh Verma Akansha Anand Pradeep Goyal Abhishek Vyas Anurag Kishor Gautam Sourav Das Shivna Tanwar Shantanu Thakur Suresh Kumar Kashyap Ashok Kumar Rawat |

| New Word as Surname | Preeti Suman |

The above-mentioned category of names, which comprises surnames traditionally associated with the so-called upper castes, can be further sub-categorized based on the varnas to which these upper castes belong.

| Sub-categories | Associated Surnames |

|---|---|

| Brahmin | Gautam, Kashyap |

| Kshatriya | Chauhan, Tanwar, Thakur, Rawat |

| Vaishya | Goyal |

Caste Names as Surnames: A Risk of Criminalization

If Dalits were to use their actual caste names as surnames, it would expose them to significant risks. In many cases, caste names used as surnames double as caste slurs. If I were to use my actual caste name as a surname, which is frequently used as a caste slur, every interaction I have with a non-SC/ST person could potentially result in violation of Sections 3(1)(r) and 3(1)(s) of the SC&ST (Prevention of Atrocities) Act, 1989 (hereinafter referred to as “the Act”). These sections prohibit insults and intimidation based on caste. Thus, the use of caste names as surnames could escalate social tensions and invite caste-based atrocities.

This reality forces Dalits to navigate a treacherous social terrain, where their very identity can become a source of vulnerability. Using caste-neutral or upper-caste surnames becomes a protective measure rather than an act of degradation.

Why Not Choose Caste-Neutral Surnames Such as “Kumar”?

The suggestion that Dalits adopt caste-neutral surnames like “Kumar” appears simple on the surface but fails to address the deeper socio-legal and cultural complexities. The practice of surname adoption is influenced by historical, social, and protective imperatives.

The assumption that caste-neutral surnames provide a universal solution ignores the layered realities of caste discrimination. Even with caste-neutral surnames, Dalits often face scrutiny based on other markers such as physical appearance, language, or place of origin. Moreover, in rural areas and traditional setups, the absence of a recognizable upper-caste surname may itself become a marker of caste identity, exposing Dalits to exclusion or violence.

Strategies for Surname Adoption Among Dalits

Dalits adopt a variety of strategies when choosing surnames, each reflecting an attempt to navigate the oppressive caste system. These strategies include using their actual gotras, modifying gotra names, adopting traditional upper-caste surnames, or foregoing surnames altogether.

Some Dalits use their actual gotras as their surnames. Gotras, which indicate familial or ancestral lineage, can obscure caste identity to some extent. However, this practice does not always guarantee protection from discrimination. In many cases, the connection between certain gotras and specific Dalit communities is well known, negating the anonymity such a strategy might provide.

Another approach involves modifying the spelling of gotras to resemble traditional upper-caste surnames. For example, a Dalit individual might alter their surname to resemble one associated with a dominant caste group. This strategy aims to shield individuals from immediate recognition as members of SC or ST communities, thus reducing the likelihood of discrimination or violence. However, such modifications are not without consequences. They often invite accusations of “degrading” upper-caste surnames, as well as social backlash from both upper-caste groups and fellow Dalits.

The adoption of traditional upper-caste surnames is a more direct attempt to escape caste-based oppression. By assuming a surname associated with social privilege, Dalits can gain access to opportunities and spaces otherwise denied to them. Nevertheless, this practice is fraught with challenges, including accusations of cultural appropriation and fears of being “exposed” as Dalits, which can lead to intensified discrimination.

A significant number of Dalits choose to forego surnames altogether. While this approach avoids direct association with a particular caste, it also erases a part of one’s cultural and familial identity. Furthermore, the absence of a surname can attract suspicion and discrimination, as it deviates from societal norms.

The Absence of Real Choice

The choices available to Dalits regarding surname adoption are not truly choices but survival strategies shaped by systemic oppression. Each option carries its own risks and consequences.

For Dalits, the primary consideration in surname adoption is protection against caste-based atrocities. By choosing names that obscure or elevate their caste status, Dalits attempt to shield themselves from violence, discrimination, and exclusion. This protective intent underscores the socio-legal precariousness of their position in the caste hierarchy.

While adopting upper-caste or neutral surnames might offer temporary relief from discrimination, it does little to dismantle the structural inequalities of the caste system. The limited social mobility afforded by these strategies often comes at the cost of cultural erasure or increased scrutiny.

Therefore, the accusation that Dalits degrade traditional upper-caste surnames ignores the socio-legal realities of caste discrimination. Surname adoption is not a matter of personal preference but a strategic response to systemic oppression. For Dalits, the choice of surname is deeply intertwined with their struggle for dignity, safety, and equality.

Legal frameworks have attempted to disconnect caste identity from surnames, but societal attitudes remain deeply entrenched. Until the caste system is dismantled, Dalits will continue to navigate these complexities in their pursuit of justice and inclusion. Rather than accusing Dalits of degrading surnames, society must confront the enduring legacy of caste-based oppression and work towards a more equitable future.

References

1. The Scheduled Castes and the Scheduled Tribes (Prevention of Atrocities) Act, 1989

2. B. R. Ambedkar, Annihilation of Caste (1936)

3. 8 Kumar Suresh Singh, Communities, Segments, Synonyms, Surnames and Titles (Anthropological Survey of India, 1996) | Link

4. Legal Names [First Name + Surname (if any)] of Scheduled Caste Applicants under the National Overseas Scholarship (NOS) Scheme | Link

5. Legal Names [First Name + Surname (if any)] of Scheduled Caste Applicants for the Civil Services Examination, 2023 | Link

6. Legal Names [First Name + Surname (if any)] of Scheduled Caste Members of Parliament (MPs) in the Lok Sabha of the Indian Parliament | Link

Leave a comment